Platinum – Part Two

Platinum/palladium prints from 31 Studio Archive

29 October 2014 – 26 April 2015

The Cloister Gallery, The Convent, Woodchester, GL55HS, UK

–

From the past for the future.

Occasionally, whilst viewing large “themed” hard-hitting, blockbuster photography exhibitions comprising room upon room full of digital printouts funkily pinned to the walls, one’s soul yearns for something altogether more beautiful, more exquisite, more thoughtful, more perfect. Quality not quantity; harmony not discord. Something quieter, calmer, more magical. Welcome to the world of 31 Studio where beauty and quality are essential components in the production of the Studio’s desirable and much sought-after platinum prints.

Photographers in the know have beaten a path to 31 Studio’s door for over 25 years now, where Paul and Max Caffell, father and son, have been producing prints using one of the finest and most beautiful printing processes ever invented. A platinum print is a permanent print, being chemically inert. The platinum image itself sits in and bonds with the fibres of the paper support rather than on an emulsion layer on top of it, as would be the case with gelatin silver printing. It will not fade, it will neither discolour nor deteriorate and, apparently, according to a lecture by Mr WH Smith delivered to the Royal Photographic Society in November 1915, will stand any amount of rough treatment such as immersion in sea or boiling water. (But perhaps better not to try this!) So it is tough but clothes that toughness with the beauty of subtle gradations of tone and a particular sort of soft luminosity with deep expressive shadows and understated highlights. An iron fist in a velvet glove.

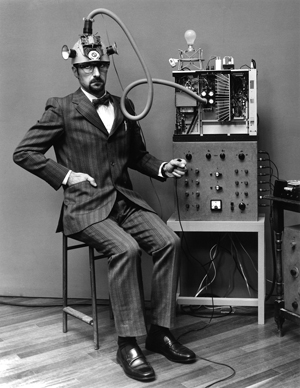

Platinum has a great affinity for skin and flesh making it a natural choice for portraiture, figure and nude studies. It gives a smooth sensuality to skin tones in very many different ways: some great examples are Bill Brandt’s Nudes, Stephane Graff’s inquisitives and self-ironic series titled Professore, Peter Dazeley’s Platinum man, and Barry Lategan’s iconic 1966 career-launching shot of Twiggy in Fair Isle: each freckle and eyelash all add to rather than detract from the humanity of the sitters.

The Douglas Brothers impressionistic Matthew is an image that truly gains from this printing technique, which emphasises its mysterious amorphous atmosphere. It is hard to believe that this is not a print by an early twentieth century Secessionist photographer, overall detail purposely obscured to enhance sublime mood.

Quite different in concept but equally intriguing is Leah Gordon’s Portrait of Chal Oska (Charles Oscar) taken at the Jacmel carnival in Haiti, a street festival celebrating voodoo, death, sex and revolution and employing the innovative use of cow horns and teeth both to conceal and to exaggerate identity.

But platinum can do detail too. No photographic process is better at depicting intricate nuances of pattern – whether from Nature or from Man. The eye of the observer is drawn by the detail of stone, brick, wood, glass and sharp text panels in William England’s Toll Bridge, Niagara, 1859, or driven straight to the soul of James Sparshatt’s series of Cuban characters.

Between 1893-1901, somewhere between 33-50% of all prints shown in the Royal Photographic Society’s annual exhibitions were platinum. Pictorialist, Fine Art and Secession photographers, amongst them Frederick Evans and Alvin Langdon Coburn, rarely used any other printing process until World War I when platinum supplies were commandeered to be utilised in military applications rather than beautiful images. Post-war, the price of platinum rose to five times that of 1900 and the process dropped out of the mainstream. But now, in the twenty-first century, museums with historic negative archives – the John Kobal Collection, George Eastman House, Getty Images, the Fondation J. H. Lartigue and Lee Miller Archives – are increasingly turning to 31 Studio to make platinum prints, and thanks to them we can admire here today the timeless pictures by Lee Miller or some examples of Coburn’s moody Whistlerian London riverscapes, alongside his Modernist images from New York’s skyscrapers.

Pamela G. Roberts

Independent researcher & writer

Curator of the Royal Photographic Society, 1982-2001